|

|

Abortion Foes Tell of

Their Journey to the Streets

|

By DAMIEN CAVE for

|

|

|

Published: October 10, 2009 |

|

|

|

Behind the Scenes

|

|

|

Click the above link to go to the New York Times web site for the Oct. 9, 2009

article on Lens Blog which includes a slide show of abortion photos. The article

is called "Behind the Scenes: Picturing Fetal Remains". |

Click the above link to go to the New York Times web site for the Oct 10, 2009

article, called "Abortion Foes Tell of Their Journey to the Streets", which

includes a video about the pro-life activists called "Foot Soldiers". A version

of this article appeared on the front page of the paper version of the NYT on

Oct. 10, 2009. |

|

|

|

|

OWOSSO, Mich. — Action means many things to abortion opponents. Lobbyists and

fund-raisers fight for the cause in marble hallways; volunteers at crisis

pregnancy centers try to dissuade the pregnant on cozy sofas.

Then there are the protesters like James Pouillon, who was shot dead here last

month while holding an anti-abortion sign outside a high school. A martyr to

some, an irritant to others, Mr. Pouillon in death has become a blessing of

sorts for the loosely acquainted activists who knew him as a friend: proof that

abortion doctors are not the only ones under duress, proof that protests matter,

and a spark for more action.

“Jim suffered the persecution for us,” said Dan Brewer, who recalls swearing at

Mr. Pouillon during one of his one-man protests in the ’90s, only to join him

later after becoming a born-again Christian. “Now we just have to go out and do

it.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A national tribute is already planned. Anti-abortion groups are calling on

protesters to stand outside schools with signs that depict abortion on Nov. 24

in 40 to 50 cities nationwide.

Some who plan to take part, like Chet Gallagher, a former Las Vegas police

officer, have been answering such calls for decades; he first got involved in

the ’80s, when every month seemed to bring a new “rescue,” another chance to

lock arms with fellow Christians and block access to an abortion clinic.

Others have arrived at the cause after experiencing personal traumas — in the

case of Deborah Anderson, an abusive childhood and then an unwanted pregnancy —

while still more fell into it through personal connections.

|

|

|

|

|

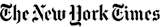

Photography by: Stephen McGee for The New York Times |

|

Anti-abortion protesters near their van at a prayer vigil in Owosso, Michigan,

in September. |

|

|

|

Together, these street activists make up an assertive minority of a few thousand

people within the larger anti-abortion movement. Neither the best financed nor

largest element in the mix, they are nonetheless the only face of anti-abortion

that many Americans see. Indeed, persistent provocation is their defining

attribute: day after day on street corners from California to Massachusetts,

they stand like town criers, calling to women walking into abortion clinics, or

waving graphic signs as disturbing as they are impossible to ignore.

Their ranks are more infused with emotion — they would say commitment — than

top-down discipline.

Ziad Munson, a sociologist at Lehigh University who has interviewed hundreds of

abortion opponents, said street protesters rarely moved into other areas of the

movement and tended to work alone or in smaller groups. Even in cases when they

form large and influential organizations, it is sometimes difficult to get

beyond the culture of passionate dispute.

|

|

|

|

|

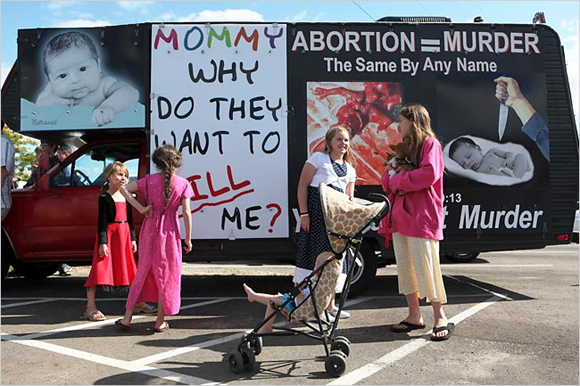

Photography by: Stephen McGee for the New York Times |

Mourners at a prayer vigil held in honor of Jim Pouillon

who was shot while protesting abortion in Owosso, Michigan. |

|

|

|

To critics, like Nancy Keenan, president of Naral Pro-Choice America, these

protesters look like bullies bent on harassment. Among those who share their

views but not their tactics, street activists have been marginalized as

attention hogs who prefer to attract outrage rather than inspiring compassion.

In the case of Mr. Pouillon, that outrage may have led to death. The police said

the man charged in the killing, Harlan J. Drake, a local truck driver, was

bothered by the signs Mr. Pouillon showed children as they came to school. The

day he was shot, Mr. Pouillon was showing a mangled fetus, part of an almost

daily effort to put abortion into the minds of his neighbors. “It’s all about

the eyes,” he used to say to fellow demonstrators. “It’s all about the eyes.”

But as the personal stories of Mr. Gallagher, Mr. Brewer and Ms. Anderson

suggest, the motivations of many protesters are more complicated. They see

themselves as righteous curbside critics, prophets warning the world with what

they describe as the horrific truth no one wants to see. They have endured

insults, threats and even estrangement from their families because they have

found what nearly every activist craves: conviction, camaraderie and conflict.

|

|

|

The Police Officer: From Civil Law to Biblical

|

|

Chet Gallagher did not plan to join the blockade at the abortion clinic in

Atlanta when he traveled there 21 years ago. But when he saw the passion of so

many Christians outside the clinic, he said, he could not resist: he ended up in

jail for 11 days, with James Pouillon and 700 others.

Three months later, Operation Rescue, the umbrella anti-abortion group, arrived

in Las Vegas, where Mr. Gallagher was a police officer. He refused to arrest

protesters, and when his sergeant suspended him, he joined the “rescuers.”

“I learned something that changed my life,” Mr. Gallagher said. “It wasn’t civil

disobedience; it was biblical obedience.”

|

|

|

|

Christian fervor nourishes anti-abortion activism like little else. Church

groups nationwide regularly ask Mr. Gallagher to speak because he chose his

spiritual beliefs over the law. Bible quotations appear on posters and on motor

homes that have become traveling billboards, and in conversation they serve as

evidentiary support, like statistics.

This is a particularly American brand of faith: confrontational and action

oriented. The most cited verses come not from the Gospels detailing the life of

Jesus Christ but from the Old Testament prophets. Mr. Gallagher said he was

inspired by Jeremiah 7, where the Lord says Israel’s “people, animals, trees,

and crops will be consumed by the unquenchable fire of my anger.”

Nancy Keenan, president of Naral Pro-Choice America, said she worried that the

emphasis on judgment provides tacit approval for violence, like the recent

killing of Dr. George R. Tiller, an abortion provider in Kansas.

|

|

|

|

But Mr. Gallagher, 60, a white-bearded father of six, disagreed. He said

Christianity must be emphasized because churches are the only institutions with

the power to put abortion clinics out of business. Like Mr. Pouillon, who often

protested outside congregations on Sunday mornings, Mr. Gallagher said far too

many Christians nodded, but did not act.

“It really can end,” he said of abortion, “if all the Christians just went out

there for seven days in a row to tell the truth peacefully.”

As for the more aggressive tactics he employs, like bringing protests to the

neighborhoods where abortion doctors live, he said they were a product of faith,

economics and politics.

|

|

|

|

Faith, because he said he believed abortion doctors deserve to be shamed;

economics because that shame might motivate them to do other work; and politics

because the era of rescues ended in 1994, after President Bill Clinton signed

the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act.

The law made it a felony to use “force, threat of force or physical obstruction”

to prevent someone from providing or receiving reproductive health services.

“That required us to use some other strategies,” said Mr. Gallagher, who left

the police force shortly after and is now director of operations for Operation

Save America in Las Vegas.

Among other things, the clinic law led to the proliferation of large

anti-abortion signs with graphic pictures of mutilated fetuses. Mr. Gallagher

said he believed that everyone, including children, should see them. “I know I

offend a lot of people,” he said. “But I’ve talked to mothers who said, ‘Because

you were there with those signs I decided to have that baby.’ “

|

|

|

|

Even in protesters’ families, not everyone agrees with the approach. Mr.

Gallagher said his wife divorced him in 1989 after revealing she had three

abortions before they met. They remarried in 1991, but Mr. Gallagher said some

of their six children had gone years without speaking to him.

“We know this is a real war and we have to fight it,” he said. “Some of our

families suffered as a result. I wish I could say it was different but it’s

not.”

|

|

|

The Survivor: An Early Gusto for a Fight

|

|

Deborah Anderson, 62, a professional test-driver for Ford with the style of a

no- nonsense grandmother, introduced herself as “someone who should have been

dead.”

“I’m an unwanted child,” she said, standing at a vigil for James Pouillon with

an anti-abortion poster peeling from overuse. “My mother couldn’t find a

back-alley abortionist, so she gave me up for adoption.”

She was 18 months old. Her sister was 4, and their adoptive mother, Ms. Anderson

and her sister said in interviews, turned out to be abusive.

|

|

|

|

Childhood in their suburb of Detroit was defined by broken bones beneath frilly

dresses, she said. The girls ran away when they could, but when friends or the

local priest visited, Ms. Anderson said, their mother chained them to poles in

the basement.

“I learned to bite and kick and scream,” she said.

That gusto for the fight is a highly valued trait in protester circles. Mr.

Pouillon earned kudos for standing with anti-abortion signs even while attached

to an oxygen tank. Ms. Anderson also told stories of long, cold protests,

insults and jail (after being arrested at Notre Dame in May when President Obama

spoke).

|

|

|

|

Her son, Jason Anderson, 35, an automobile engineer, said that as a teenager, he

learned to take pride in his mother’s passion when he saw her enduring abuse for

holding a graphic sign. “She’s really trying to open up people’s minds to the

horrific nature of this,” he said.

The most repeated anecdotes involve abortions averted. Ms. Anderson recalled

what she said was her first triumph. It was the early ’80s. After becoming

pregnant with a boyfriend while separated from her husband — and deciding to

have the baby despite friends’ advice to abort, she said — she was a single

mother with a bumper sticker on her Chrysler Fifth Avenue that said “the heart

beats at 24 days for an unborn child.”

One day in a parking lot near her home, Ms. Anderson said, a woman came up to

her and said she had been on her way to get an abortion when she saw that simple

statement and changed her mind. “There was a 2-year-old in the back seat,” Ms.

Anderson said.

|

|

|

|

At her home in Memphis, Mich., other examples followed: of two girls from Ohio

who left an abortion clinic and, she said, told Ms. Anderson that her presence

had persuaded them had not gone through with it; of a young man who knocked on

her door in the dead of night, after seeing anti-abortion signs in her window.

Then Ms. Anderson pulled out a black cassette recorder. Sitting on a red couch a

few feet from two abortion posters, she replayed what she said was a voicemail

message from several years ago. An older woman, sounding unsure and emotional,

said she wanted to thank her because “you was at the clinic, and really helped

my daughter.”

Ms. Anderson smiled. “I can’t tell you how many babies have been saved because

of abortion protesters outside the abortion mills,” she said. “That’s what it’s

all about.”

|

|

|

The Friend: Drawn to the Cause

|

|

Within months of becoming a born-again Christian, Dan Brewer says, he knew he

had to make things right. When he saw James Pouillon on a corner in Owosso one

day, he stopped his car, walked over and asked forgiveness for having accosted

him.

“I put my head on his shoulder and cried,” he said.

It was the beginning of what would become an alliance. Ziad Munson interviewed

abortion opponents for a book, “The Making of Pro-Life Activists,” and said most

people entered the movement through social connections and only later developed

an ideological commitment.

|

|

|

|

Mr. Brewer exemplifies the process. He did not have much passion for the cause

early on, he said, but the resistance and support he experienced alongside Mr.

Pouillon led him to more research and activism.

He said there was something rebellious, something American, about standing up

against abortion. In the past, he had occasionally held signs with bible verses

emphasizing love, but they did not lead to as many conversations.

Or conflicts — like the time a man drove up on the sidewalk, running over Mr.

Brewer’s sign and forcing him to jump out of the way, he said.

|

|

|

|

“I don’t want to say the conflict is fun, because it isn’t,” said Mr. Brewer,

40, an easygoing state pool champion with an earring high in his left ear. “But

the interaction is fun, to be able to talk to people who take the time to listen

to what you have to say.”

A layoff last year from his job at a boat factory pushed him further. He joined

Mr. Pouillon about three times a week, he said, partly for the camaraderie and

partly — like other anti-abortion protesters — because he had come to see

attention and opposition as proof of impact.

He just never thought it could turn deadly. Nor did his son Cameron.

|

|

|

|

Now 16, the second oldest of Mr. Brewer’s five children, including a foster

child, Cameron was at school when the shooting happened at a nearby corner. He

ran there, fearing for his father, instead finding a bloodied friend. “I got

down next to him,” Cameron said. “I counted four bullet holes.”

The Brewers said they did not expect more violence. And like hundreds of others,

they said they planned to keep Mr. Pouillon’s efforts alive. Mr. Brewer may not

be there as often, because he is taking nursing classes, but Cameron said he was

eager to fill the void.

“I thought it was cool that he did what he did,” he said. “Now that he’s dead,

it makes you want to do it more.”

|

|

|

A version of this article appeared in print on

October 10, 2009, on page A1 of the New York edition. |

|

|

|

|

Behind the Scenes (Oct. 9 Article)

|

|

The Coup (Intro)

|

|

|

|

|

|