|

|

Behind the Scenes:

Picturing Fetal Remains

|

By Damien Cave for

|

|

October 9, 2009

|

|

|

|

Behind the Scenes

|

|

|

Click the above link to go to the New York Times web site for the Oct. 9, 2009

article on Lens Blog which includes a slide show of abortion photos. A copy of

the NYT article is below on this web page. |

Click the above link to go to the New York Times web site for the Oct 10, 2009

article, called "Abortion Foes Tell of Their Journey to the Streets", which

includes a video about the pro-life activists called "Foot Soldiers". A version

of this article appeared on the front page of the paper version of the NYT on

Oct. 10, 2009. |

|

|

|

|

|

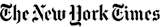

Photography by: Stephen McGee for The New York Times |

|

|

|

"Maybe fifty percent of the graphic images of

abortion victims that you'll find online are probably my photography." said

Monica Migliorino Miller, Associate Professor of Theology at Madonna University

in Orchard Lake, Michigan. Dr. Miller is an active member of the anti-abortion

movement. |

|

|

|

|

|

The photographs are graphic and detailed, showing the fingers or toes of aborted

fetuses whose entire frames are no bigger than a cellphone. Since the mid-

1990s, they have appeared all over the country — carried as posters by

protesters, handed out with pamphlets or, in some cases, mounted like billboards

on the sides of trucks.

Like many others, I often wondered about the source of these images. Who took

the pictures? Where did the fetuses come from?

|

|

|

|

I had a chance to find some answers while reporting in late September on the

death of

James Pouillon, the anti-abortion protester who was shot and killed in

Owosso, Mich. [See Saturday's

presentation

on the subject in The New York Times.]

Mr. Pouillon was holding an anti-abortion sign at the time, with a baby on one

side and an abortion on the other. At his memorial service, I met Monica

Migliorino Miller, who told me she had a lot to share about the use of abortion

imagery.

Monica Migliorino Miller, a theology professor at

Madonna

University and the director of

Citizens for a

Pro- Life Society, said she had firsthand experience retrieving fetuses

after abortions and photographing them. When we met two days later in her

university office, she handed me proof: a series of 4-by-6-inch prints that she

shot, which have been turned into portraits by Stephen McGee.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first image in the pile gave me a clue to the source. It showed a cardboard

box with six or seven large, sealed plastic bags with something red inside.

There were names on the bags in black ink and, on the box, there was a date

written with felt-tip marker: Feb. 27, 1988.

Mrs. Migliorino Miller said this was one of the many boxes filled with fetuses

that she, her husband and several others pulled 21 years ago from a loading dock

in Northbrook, Ill., a suburb of Chicago. Acting on a tip, between February and

September of 1988, she said they retrieved around 4,000 fetuses that had been

shipped there from a dozen or so abortion clinics nationwide. (A

protracted lawsuit tied to their

efforts

ended in 2003.)

Mrs. Migliorino Miller said the boxes filled spare rooms in her apartment and

others for nearly a year. “We didn’t feel we could put them in storage,” she

said.

In 1988, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, archbishop of Chicago, presided over a

funeral for around

2,000 of the fetuses. Activists buried many others.

|

|

|

|

But for Mrs. Migliorino Miller, a diminutive woman of deliberate mien, there

were more discoveries. Last year, she said she found 23 fetuses in trash-hauling

bins outside two Michigan abortion clinics, leading to a

state investigation of the companies’ removal procedures; in 1987, she said

a tip led her to a Chicago alley with dozens of boxed-up fetuses in a

trash-hauling bin.

That was when she took her first fetal pictures. She described her initial

motivation as journalistic. “We felt it was very important to make a record of

the reality of abortion,” she said.

The process was a challenge: the fetuses, hard to handle; the scent of the

formaldehyde solution, enough to burn the nose. Shooting could only be done up

close. She recalled renting expensive macro lenses to get within millimeters of

the fetuses.

|

|

|

|

She pointed to one of her snapshots showing a tiny hand with visible wrinkles.

“In order to get that detail,” she said, “you need to get a camera right on top

of that.”

She defended protesters’ use of blown-up imagery — sometimes as large as

billboards — as necessary and justified. “In order to see the humanity and

beauty of something so small, you have to enlarge it,” she said. “Otherwise, the

baby is invisible and dismissed.”

Over time, however, her views on which images are appropriate have evolved. She

no longer sees gory pictures showing blood or organs as acceptable. She has

tried harder to shoot younger fetuses, because that’s when most abortions take

place, and she said she also believes that the most graphic images should not be

deliberately directed at children because “they can’t intellectualize what

they’re seeing.”

|

|

|

|

Her pictures from last year reflect the new approach. They are shot with a

purple background of fine wrapping paper, without any blood visible.

“I want to show there’s beauty and humanity in the unborn child,” she said.

“There should be a sense of pity.”

Vicki Saporta, president of the National

Abortion Federation, said in an interview that most of the images displayed

on street corners are problematic because they depict late-term abortions.

“Almost 90 percent of abortions take place in first trimester, where the

pregnancy bears no resemblance to these photos,” she said. She added that the

pictures “are designed to evoke an emotional response to manipulate women not to

choose abortion, and to manipulate the public to support banning abortion.”

|

|

|

|

From within the anti-abortion movement comes the opposite criticism. Some

consider Mrs. Migliorino Miller’s effort to inspire compassion a sign of too

much concern for the audience. “It’s a nice sentimental argument,” said Flip

Benham, director of

Operation Rescue/Operation Save America. “What’s important is truth to us;

that this is the truth.”

I found Mr. Benham while searching for the history of “Malachi,” perhaps

the anti-abortion movement’s most famous photo. [Note: photograph in this

pdf document contains a graphic image.] Mr. Benham took my call at a protest in

Charlotte, N.C., where he said photos of Malachi had helped save seven babies

that day.

A brochure from Operation Save America laid out some of the background on

Malachi, which Rhonda Mackey, the activist who found it, named after the last

book of the Old Testament because it means “messenger.” The brochure said it was

a “baby boy found frozen in a jar with three other children at an abortion mill”

in Dallas in 1993.

|

|

|

|

Mr. Benham told me he was there that day and saw Ms. Mackey take the jar, one of

dozens preserved in flip-top freezers. It was another month, Mr. Benham said,

before the pictures were taken because he was in jail for a separate retrieval

mission.

The brochure leaves this detail out. It says simply, “We brought the jar to Dr.

McCarty, a wonderful Ob-Gyn in Dallas, who put the pieces of this baby and the

others back together.”

Mr. Benham said a video of that process, not available online, shows Dr. McCarty

weeping as he works. But with other fetuses in the jar, I asked, how did you

know all the parts in the image belonged together?

|

|

|

|

Mr. Benham said the fetuses were at different stages of development, and he

trusted Dr. McCarty’s judgment. (Dr. McCarty has since died; Mr. Benham said he

could recall only the photographer’s first name, Marco, and did not know how to

reach him.)

Was there a date on the jar or any way of knowing how long it had been stored?

“No,” Mr. Benham said.

|

|

|

|

Other questions arose. How did you know for sure that Malachi was not a

miscarriage? How did you know the damage to the fetus did not come from simple

decomposition, or the month that it was outside the freezer?

Mr. Benham said there was no doubt in his mind that the image captured the truth

of abortion because Malachi was found at a clinic dedicated to abortions. He

cited the mark by Malachi’s right ear. “You can see that, it’s forceps,” he

said.

Mrs. Migliorino Miller, in our interview at her office, had defended the photo

of Malachi because she said it emphasized “the humanity” of the fetus. When I

later described the picture’s origins, she said she was surprised. Joe

Scheidler, a friend and fellow activist who uses some of Mrs. Migliorino

Miller’s images on Face the Truth

tours, said she has precisely documented each fetus she photographed, by date,

location and — with the help of a doctor — gestational age.

|

|

|

|

Mrs. Migliorino Miller acknowledged that not everyone in the anti-abortion

movement was as careful. But with Malachi, she said, “There’s no way you can

deny that’s a baby that suffered a trauma.”

For the cause, it works. “You have a whole baby,” she said. “That makes it a

very valuable and powerful image.”

|

|

|

|

Journey to the Streets (Oct. 10 Article)

|

|

The Coup (Intro)

|

|

|

|

|

|